Humanitarian Trip to Poland Provides Life-Changing Help for Ukrainian Refugees

Audiology and speech-language pathology students also spend time working with Polish special needs students during nine-day mission trip to Krakow

The MGH Institute’s humanitarian work overseas was a big draw for audiology student Morgan Sanborn when she decided to enroll. Same with Payton Kober. They were among the first to sign up to work with Ukrainian refugees during a trip that took place over winter break.

For Abigail Wenner, the chance to help Ukrainian refugees with their hearing was personal.

“I have family members that were affected by the war,” said Wenner, “and knew as soon as I learned about this ongoing effort that this was something I wanted to do.”

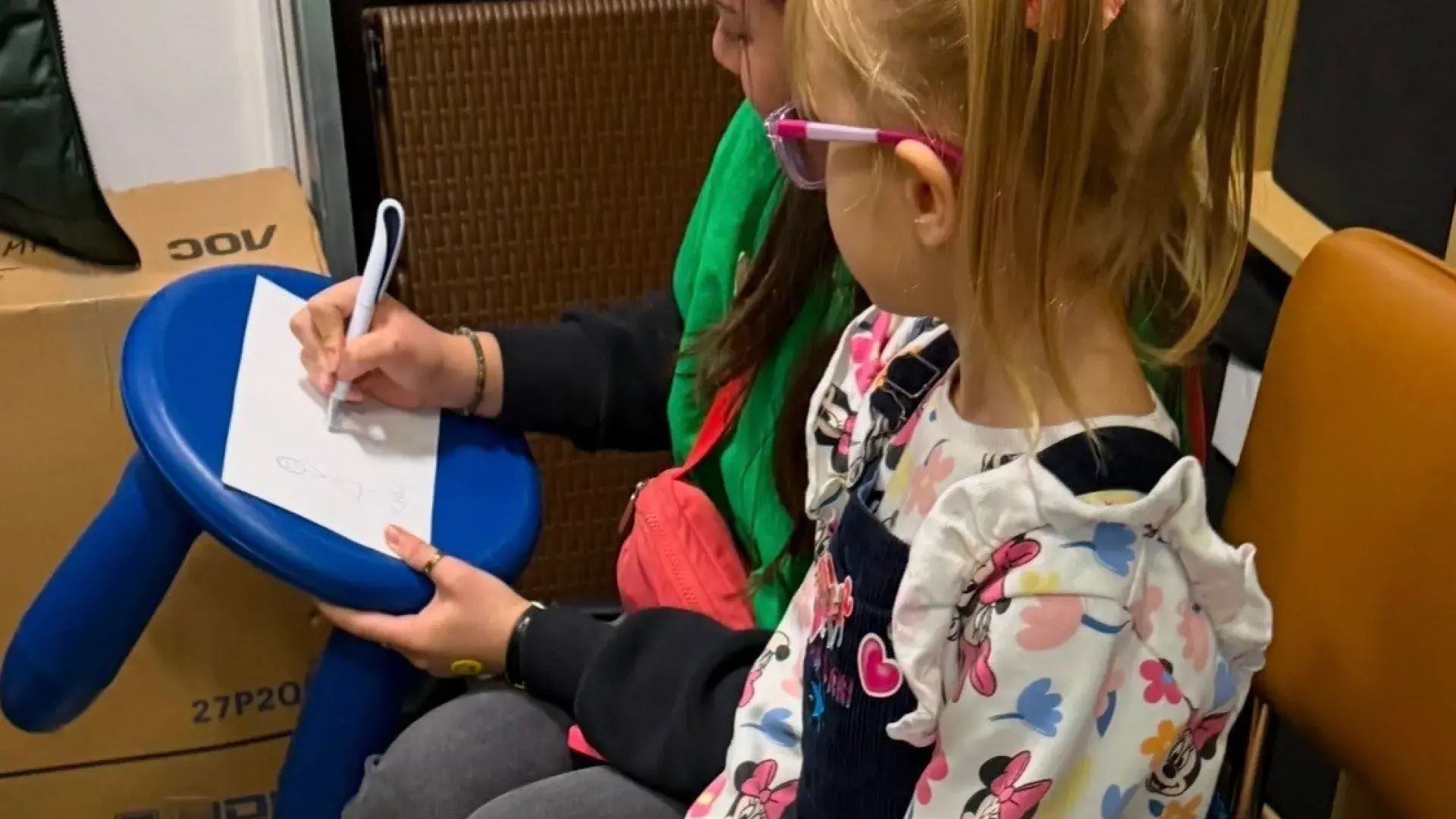

The ongoing effort of bringing MGH Institute students overseas is organized by Audiology Professor King Chung, who led a contingent of seven students on a nine-day service trip to Krakow, Poland, just before Christmas. They tested the hearing of more than 40 Polish students with special needs on the first day, then treated a flood of refugees who fled their native Ukraine when Russia invaded their country nearly three years ago.

“We’re using our profession to fight social injustice, especially in the war zone,” said Chung, who has led six service trips to Poland. “People are only talking about how many people died but they don't talk about how many people had tinnitus, and how many people suffer from hearing loss because of the shelling and bombings. We’re doing what we can to fight this social injustice.”

For Sanborn, utilizing interpreters and a translation app on her phone to help Polish students and Ukrainian refugees was both educational and illuminating.

Student Views: Poland Trip

“Working in the field is fundamentally different from working in a clinical setting,” noted Sanborn. “We were limited in the amount of equipment we could bring, which required a completely different mindset. If something went wrong, we had to adapt quickly, think creatively, and come up with alternative solutions—approaches we might not consider in a fully equipped clinic back home. It was an incredible experience—'amazing' is truly the one word that captures it.”

“One of the reasons I came to the MGH Institute is the humanitarian work that Dr. Chung does,” said Kober. “From the moment I heard about the trip to Poland, I knew it was an opportunity I needed to embrace. Upon arriving in Poland, it became immediately clear that this was where I was meant to be and exactly what I was supposed to be doing. While I do not always know what my future will hold I am certain that humanitarian work, like what we did in Poland, will be an integral part of it.”

Kober was joined by fellow audiology students Wendy Vong, Sanborn, and Wenner and Speech Language Pathology students Kelly Marshall and Jacqueline Dwyer.

“We did have interpreters but there were multiple stations and only so many to go around,” said Marshall, a speech-language pathology student who was in charge of the documentation and administration work. “So, we had to be flexible kind of figure it out. I had Google Translate on my phone, and I had the Ukrainian keyboard on my phone if a patient needed it to talk to me.”

Also joining the mission trip was Burgundy Bisson, an audiology student from California State University, Los Angeles, who was told about the trip by her mentor who went on it last year.

“I’d be lying if I said it wasn’t daunting,” said Bisson. “I was joining a group of students from one of the top audiology programs, and I couldn’t help but question if I’d measure up. I knew this was an opportunity worth taking.”

Indelible Impact on Patients

“It took us a day or two to establish an efficient routine and determine how best to collaborate as a team,” said Sanborn. “Once we found our rhythm, we were managing to see 12 to 14 patients daily. For a group of individuals who had never worked together before, it was remarkable how quickly we became a cohesive unit. The pace was extraordinary—I had never seen so many patients in a single day.”

The patients ranged from newborns to those in their 90’s; the services ranged from testing to hearing aid services. Many came in with hearing damage from the war or had never had their ears looked at before.

“We encountered an older gentleman with an unusual object lodged in his ear, the nature of which we couldn’t immediately determine,” recalled Sanborn. “Our educated assumption was that it might have been fragments of metal, possibly embedded as a result of a bombing or similar incident. These were individuals seeking professional care for the first time, finally having someone examine their ears.”

The students calibrated the audiometers, tested hearing, made impressions and instant earmolds, hearing aids, and counseled how to use them. Patients were taught how to care for, clean, and troubleshoot their devices, and received six months of supplies (batteries, cleaning tools, and replacement parts) to last until August, the next time Chung and her students return to Krakow.

“We saw an 80-year-old woman who started crying as soon as she put on the hearing aids, and the group of us working with her were startled thinking to ourselves, ‘Oh, my gosh! What's wrong? What's happening?’” recalled Kober. “She proceeded to share with us that she had never heard her own voice before, so then we all started crying. It was at that moment that we knew we had forever changed her quality of life for the better. A transformative moment for her and all of us who shared this experience with her.”

A similar breakthrough occurred with an 88-year-old woman who lost nearly all of her hearing at the age of five because of meningitis. She never learned sign language or how to read lips and had been communicating through the written word her entire life.

“We were the first to ever treat her hearing loss, so she had not heard speech clearly in over 80 years,” recounted Wenner. “It was hard for us to comprehend how she could have gone her whole life without being treated. And even once she came to us, it took a long time for us to convince her that we wouldn't be taking the hearing aids back or requiring payment. After putting the hearing aids on for the first time, she was able to have full conversations in Russian. To see the difference we made in her life was really something I’ll always cherish.”

A sentiment echoed by audiology student Wendy Vong: “We encountered so much gratitude and kindness on this trip. Multiple times, patients kept telling us how thankful they were for the services we gave. Some of them even returned to give their blessing and tell us about the new sounds they had heard and how different their lives were going to be”

The stories and impact were never ending. There was the second grader who was about to be placed in a special education class because she did not respond to her parents and teachers well. So, they suspected she might have intellectual disability and they were evaluating her to go to a special education school. Turns out all she needed was hearing aids.

“After we fitted her with high performance hearing aids, she started conversing with everyone and she is doing well in a mainstream school,” said Chung, recipient of the Humanitarian Award from American Academy of Audiology. “This story reminded us about the importance of hearing. The impact of hearing loss is great, and it affects the communication, educational attainment, and a lot of daily activities. A pair of high-end and appropriately fit hearing aids may cost approximately $5000, but the change of a child’s life trajectory for the better is priceless!”

For Wenner, whose aunt is from Kyiv, the stories of the patients she worked with strengthened her convictions to spreading awareness about the social and emotional impact of hearing loss.

“What many people don’t know about noise-induced hearing loss is that it can dramatically change the way someone experiences the world around them,” said Wenner. “For several of the patients we saw, a bomb went off, their ears started ringing, and all of the sudden their world seemed to get smaller and lose the detail and vibrancy we often take for granted — the birds chirping, the sounds of children playing, the familiar qualities of their loved ones' voices. They attributed it to ‘shell shock’ and had accepted that that’s just how things were now. But once we turned the hearing aids on, and they could hear papers rustling and the conversations going on around them, you could see on their face that the familiar sounds of the world they knew before the war were coming back. And getting to see that is an honor I’ll never forget.”

Enduring Influence on Students

“It was just incredible hearing how their lives have just been completely displaced, and hearing how their families and their loved ones are affected by it,” said Marshall. “I think we did a great job of creating a safe and comfortable environment because these people are telling us their stories and being very vulnerable with a bunch of foreigners who don't speak their language.”

Jackie Dwyer, another speech-language pathology student, said the experience enhanced her understanding of noise-induced hearing loss and congenital deafness, both critical for effective collaboration with audiologists.

“Beyond the technical skills, the experience allowed me to consider the unique stories and backgrounds of the individuals I worked with, inspiring me to help them achieve their full potential,” remarked Dwyer. “This transformative journey profoundly impacted my personal and professional growth, deepening my empathy and reinforcing the importance of compassionate care. It served as a powerful reminder of how our profession can have far-reaching effects when we use our skills to serve others.”

Bisson said the experience reminded her of how easy it is to get caught up in the cycle of exams, grades, externships, and lose sight of why you’re in school in the first place.

“This trip was a wake-up call—it reminded me that audiology is about human connection,” noted Bisson. “It’s about the patients who trust us with their care and the colleagues who make the chaos manageable - and sometimes even fun. Being part of this MGH IHP team, navigating challenges together, and building real relationships brought me back to the core of why I chose this field in the first place. It’s not about having all the answers—it’s about showing up, connecting, and making a difference where it matters most.”

Along with the audiological attention, safe spaces and tender moments were abundant.

“When you're communicating with someone who has a language barrier, you make a connection that goes beyond language,” observed Kober. “Often, it was about being a source of comfort and reassurance—offering a steady hand to hold during moments of uncertainty, especially since many of the individuals we saw were without the support of their families. I came to deeply appreciate how much warmth and compassion could mean in those vulnerable moments, and how it could truly make all the difference.”

Added Vong, “I don’t think there is anything more motivating and rewarding than seeing the direct impact of our work, especially those who have endured the hardships of displacement and war. Hearing everyone’s stories was eye opening and has inspired me in both my professional and personal life.”

For Bisson, the non-stop work was fulfilling in a way she hadn’t experienced before.

“We weren’t just testing hearing or diagnosing patients—we were building connections, learning how to adapt to unique challenges, and seeing the immediate impact of our work,” Bisson shared. “For me, the most surprising part was how much I learned outside the clinical work. It was the conversations, the shared meals, and even the late-night laughs with the MGH students that stuck with me. They were smart, hilarious, and passionate, and by the end of the trip, I felt less like an outsider and more like part of the team.”

Funding a Humanitarian Trip

It takes a village to undertake a trip like this, and it starts with donations. Hearing aid manufacturers, equipment, and accessory suppliers, and an earmold manufacturer donating equipment and services that included ear molds, equipment calibration, and high-end hearing aids. Central Michigan University's Student Audiology Student Association raised money to pay for an interpreter and to ship a piece of vital equipment to Poland and back. Partners at the Jewish Community Center of Krakow made all the arrangements with the Ukrainian refugees and interpreters.

“It’s a concerted effort — a lot of people supported it,” said Chung, who has led humanitarian research and service trips to eight countries on five continents. “My students and I are the people to provide the services. There’s a lot of goodwill behind the whole mission that makes it all possible.”

Goodwill and good hearts restoring one of the five senses that provided a new lease on life.

“The people were genuinely astonished that we were providing hearing aids and services at no cost, and their gratitude was overwhelming,” said Sanborn. “It was incredibly rewarding to assist them in improving their hearing, no matter how big or small. The experience was profoundly moving—tears were shed on both sides, creating a deeply emotional and heartwarming connection. I feel truly fortunate to have had the opportunity to make a meaningful difference in someone’s life.”

While the students saw the Auschwitz concentration camp and toured an underground salt mine on their days off, it was the images of their impact that they took home.

“I think this trip changed my outlook and reminded me that audiology is more than about technology and procedures; it is about human connection, communication, and restoring a sense of normalcy in people’s lives,” concluded Kober. “This experience has profoundly deepened my appreciation for the vital role audiologists play in transforming lives. The firsthand encounters and lessons I gained in Poland will forever hold a special place in my heart, shaping both my perspective and my purpose.”

Do you have a story the Office of Strategic Communications should know about? If so, let us know.