Panel of health professionals discusses shifting perspectives and roles when provider becomes patient during recent Caldwell Lecture

Healthcare professionals know a lot about caring for patients, but what happens when the patient is a healthcare professional? That was the question considered during the recent Ann W. Caldwell President’s Interprofessional Lecture sponsored by the Center for Interprofessional Education and Practice (CIEP).

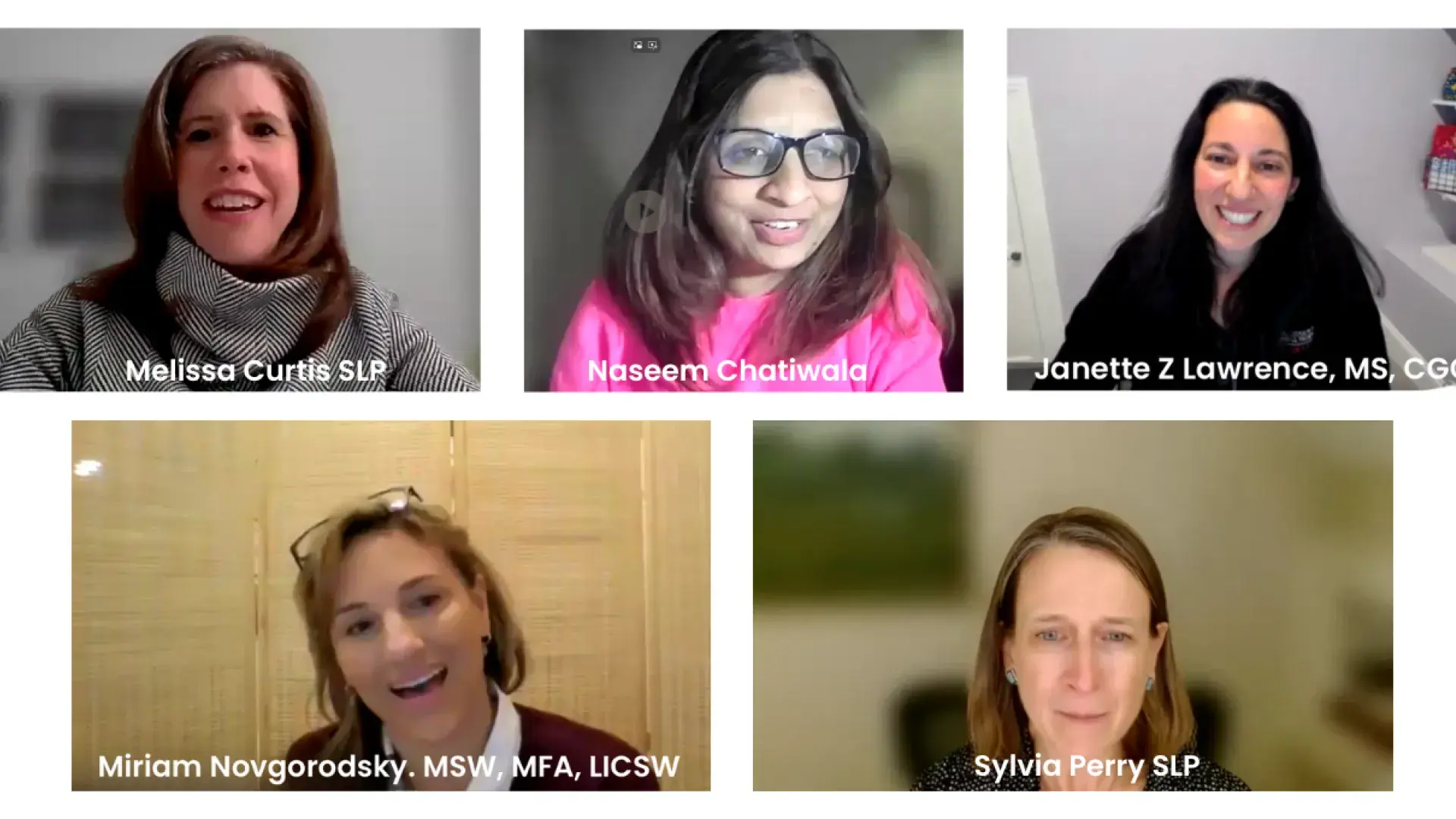

Inspired by the CIEP Common Reading Program book from 2023-2024, “When Breath Becomes Air” by neurosurgeon Paul Kalanthi, who wrote about his experience facing metastatic lung cancer, the virtual panel discussion explored what happens when a healthcare professional becomes a patient from both the patient and healthcare provider’s perspective. Moderated by Janette Lawrence, an adjunct assistant professor at the MGH Institute and a genetic counselor at the MGH Center for Cancer Risk Assessment, the lecture featured four panelists who shared their views on the medical, social, and ethical considerations of a healthcare professional as a patient.

In her opening remarks, MGH Institute President Paula Milone-Nuzzo explained the history of the Caldwell Lecture, named after the MGH Institute’s fourth president who attended the lecture, along with 457 students, faculty, staff, alumni, and community members.

“We will all be in this space at some point in our careers, and this discussion sets the table for further reflection on this important issue,” said Milone-Nuzzo. “We also just started the second year of our strategic plan, and as a community, we recommitted our Institute to the core value of interprofessional education and justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion. These values drive the way we treat each other, our day-to-day work and the goals we set for educational programs, our research and our community engagement. This program is one example of how we live our values.”

Moving from Provider to Patient

When Naseem Chatiwala MSPT ’04, DPT ’07 had her biopsy, she was sure it would be negative. It wasn’t.

“It hit me like a tidal wave,” recounted Chatiwala.

Still, she thought she would have an easier time navigating the treatment process because she was a healthcare professional, but that was sometimes more of a hinderance than a help. Her first appointment had to be rescheduled because she didn’t realize the doctors at Massachusetts General Hospital needed her biopsy slides.

“I wish I had asked what is needed for this appointment,” said Chatiwala. “One of the hardest parts of the journey was reconciling my identity as a healthcare provider and a new role as a patient. I wanted to be a good patient and avoid being seen as difficult. I felt like there was a constant need to sound intelligent. This led me to suppress some of the questions I had for the surgeon. I feel like I was fighting myself and thinking, ‘I don’t want to ask it because it is a very basic question. I’ll go home and do a Google search.’”

Her own experience also added to her anxiety rather than making it easier.

“I was terrified of the surgery, but more than surgery, I was more terrified of the complications that could arise,” Chatiwala shared. “As a physical therapist, I’ve seen so many things and know so many things can go wrong.

Caring for a Healthcare Professional

Chatiwala met her surgeon before the procedure and that helped because the doctor recognized Chatiwala as a health professional and treated her as part of the team. She also let Chatiwala know that the team would take care of some of tasks that she had been handling, such as making appointments.

“I thought I had to call the doctors and make appointments, but my surgeon said, ‘No, my team will take care of that.’ That day, that word team literally put tears in my eyes. It was just so impactful and powerful to hear that ‘My team will take care of you’.”

Having a team around her made Chatiwala more comfortable, something that is an important part of treating healthcare professionals, according to Sylvia Perry MS-NU ’02, a nurse practitioner in surgical oncology at Mass General’s Avon Breast Center.

“It is a big step for a healthcare provider to cross the threshold into an exam room and take their armor off,” said Perry, “Having an openness and making an intentional effort to make that space feel comfortable, to let them know, ‘What I say in this visit is confidential and you are my provider and I’m able to let myself open up.’ As a provider, you need to also just remind them that this is their time, this is their space, no question is off the table.”

Miriam Novogrodsky, an oncology social worker for Mass General Brigham, agrees.

“I think one of the challenges I find is to make sure that we let them have the space and encourage them and somehow finding that sweet spot where they allow us to care for them,” said Novogrodsky. “And naming that and talking about that, letting them ask the questions that they’re a little afraid of asking because they’re concerned that we’ll make them into not as good a patient.”

One way to do that is to focus on compassion.

“If you think about the root of compassion, the Latin word means ‘to suffer with,’ — to share the experience with the person in the room,” added Perry.

Shared Decision Making when the Patient is a Health Professional

According to Perry, it is also possible that healthcare providers might treat fellow healthcare providers differently when they are patients.

“No matter what type of healthcare provider, they need to make sure the patient is the patient,” said Perry. “It is important to speak to the patient healthcare provider in the same way you would speak to anyone.”

That includes giving them information, even if it seems like the patient will already know it. That is something Chatiwala took from her experience as a patient.

“I have a lot of patients who are physicians and sometimes I feel like I don't educate them as much thinking they know this, right?” said Chatiwala. “So, I might use a little bit more medical terminology sometimes with them. Now I think I have changed the way I do it.

“I had my own physical therapy for my shoulder range of motion and the physical therapist asked me, ‘Naseem, do you need a handout for exercises and stretches? And I'm like, sure, yes.’ Those three exercises, which were on the handout, I know them really well, and I give them to a lot of my patients. But there was just some power in that handout saying Naseem Chatiwala, five times, 10 times, twice a day.

“And I think it just increased my compliance with doing those because now I have a paper in my hand, and I need to do it. And so I think going back to now my patients who are physicians themselves, I have changed the way I educate them, even though they know it, because I think that the reminder of repetition and clarity is vital no matter who the patient is.”

As the moderator, Lawrence shared an example of a patient thinking invasive meant something different than it does in their field. This is a case where Novogrodsky recommends making sure the patient is understanding the information as it was intended.

“I ask every patient I work with their understanding of their diagnosis and their understanding of their prognosis and their treatment,” said Novogrodsky. “Within that is the piece of what is the language and how are they hearing it. I like that as a way to get their understanding and that’s a helpful jumping off point for what’s possibly scaring or concerning them.”

Healthcare professionals also have to make sure they don’t overestimate their patients’ understanding simply because they are also healthcare providers. Melissa Curtis CSD ’14, a speech pathologist at Massachusetts General Hospital who serves on the hospital’s ethics committee, shared an example of a patient being treated in the ICU who was delirious.

“I’ve witnessed medical teams have the real deep desire to respect a patient’s autonomy and their knowledge base as a fellow physician, so there have been times where we’ve overestimated their ability cognitively to elect choice for themselves,” said Curtis. “It is really important not to overestimate that when someone’s vulnerable.”

That is one bias that can come up when treating another healthcare provider but there are others; Curtis recommended guiding ethical principles (e.g. autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence) to help students as they enter their chosen fields.

“We’re all human and we all have questions or love for the person that we’re there supporting, or worries as the patient, or empathy as the provider who is trying to help their patient who’s struggling with something. And I think remembering that, and always weaving that into your clinical practice as you take on that provider hat when you care for another healthcare provider.”

Following the lecture, students gathered in small groups to reflect on the learning from the panel and consider strategies that they will integrate as future health professionals. The Caldwell Lecture, planned annually by the CIEP and Interprofessional Activities Committee, is a valued IHP tradition, empowering students, educators, and health professionals to reflect on compassionate care and consider how collaborative, client-centered teams can work together to advance health outcomes.

Do you have a story the Office of Strategic Communications should know about? If so, let us know.