Reading after hemispherectomy in children has rarely been studied, and never integrating the brain

For children who have epilepsy, experiencing multiple seizures a day is debilitating (and sometimes life-threatening) and disrupts not just the flow of daily life but also development, learning, and academic progress. In cases where medication fails and the seizures come from just one side of the brain, a unique neurosurgical procedure called hemispherectomy may be recommended.

In hemispherectomy, the brain hemisphere that is the source of the seizures is fully removed or disconnected from the rest of the healthy brain. But how does this affect a child’s skills and abilities? How well can a child read and speak when half of their cerebral cortex is missing?

Now a study led by Brain, Education, & Mind (BEAM) Lab director Joanna Christodoulou is about to find out. The study is lasered focused: What is the potential of a single hemisphere of the brain to support reading and language after this surgery?

Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and a variety of neurocognitive assessments, Dr. Christodoulou and her team will investigate how reading skills relate to the unique brain structure of children and young adults who have undergone hemispherectomy. Their findings will offer insights into reading skills and development for children affected by epilepsy or neurosurgery as well as those who experience developmental reading and language disabilities.

Dr. Christodoulou has studied reading skills after hemispherectomy in the past, so working with children in the hemispherectomy population is not unfamiliar to her.

“The good news is that even when half the brain is purposefully made non-functional, the remaining brain hemisphere still demonstrates potential for reading,” said Christodoulou. “This may sound surprising, given the well-established idea that the left hemisphere is the dominant seat of oral and written language skills in humans with contributions of the right hemisphere as well. But this concept is most applicable to adults and children who have spent their developing lives seizure-free and with two cerebral hemispheres.”

There are two key differences this study has from her previous research with this community.

“We haven’t had the opportunity to collect brain imaging data with participants before,” Christodoulou shared. “And we are thrilled that so many participants joined us for this study.”

Christodoulou’s team has the largest sample of participants post-hemispherectomy to be scanned for prospective research exploring language skills. The research team completed brain scans of participants as they were reading, a time-intensive effort that has never been accomplished on this scale in the population.

“No one, to my knowledge, has done brain scans while children post-hemispherectomy have been reading at this scale,” said Christodoulou.

“We care about this community of students who are in a special situation. They are on the other side of intensive surgeries and medical recovery; when they go to school, few professionals know what to expect or how to help them,” she continued. “People can make a lot of incorrect assumptions about children who have had a hemispherectomy. While most have some physical disabilities following surgery, which is visually apparent, these children are very resilient and capable when given the context and resources to thrive. We want to elevate that potential and offer these children and their educators knowledge and resources for fostering reading development. We want to educate the community so that no one discounts children’s intellectual capacity or potential for learning post-hemispherectomy. It is so important to better understand reading outcomes and associated brain structure and function post-hemispherectomy and to share that knowledge with educators, families, clinicians, and other community members.”

Christodoulou received National Institutes of Health funding to conduct this research, and she’s working with MIT’s Imaging Center and its director, John Gabrieli, with whom she’s collaborated through the years.

“The partnership between the Gabrieli Lab and my team has been so fulfilling and productive, and I am thrilled to have worked on this special study together,” says Christodoulou.

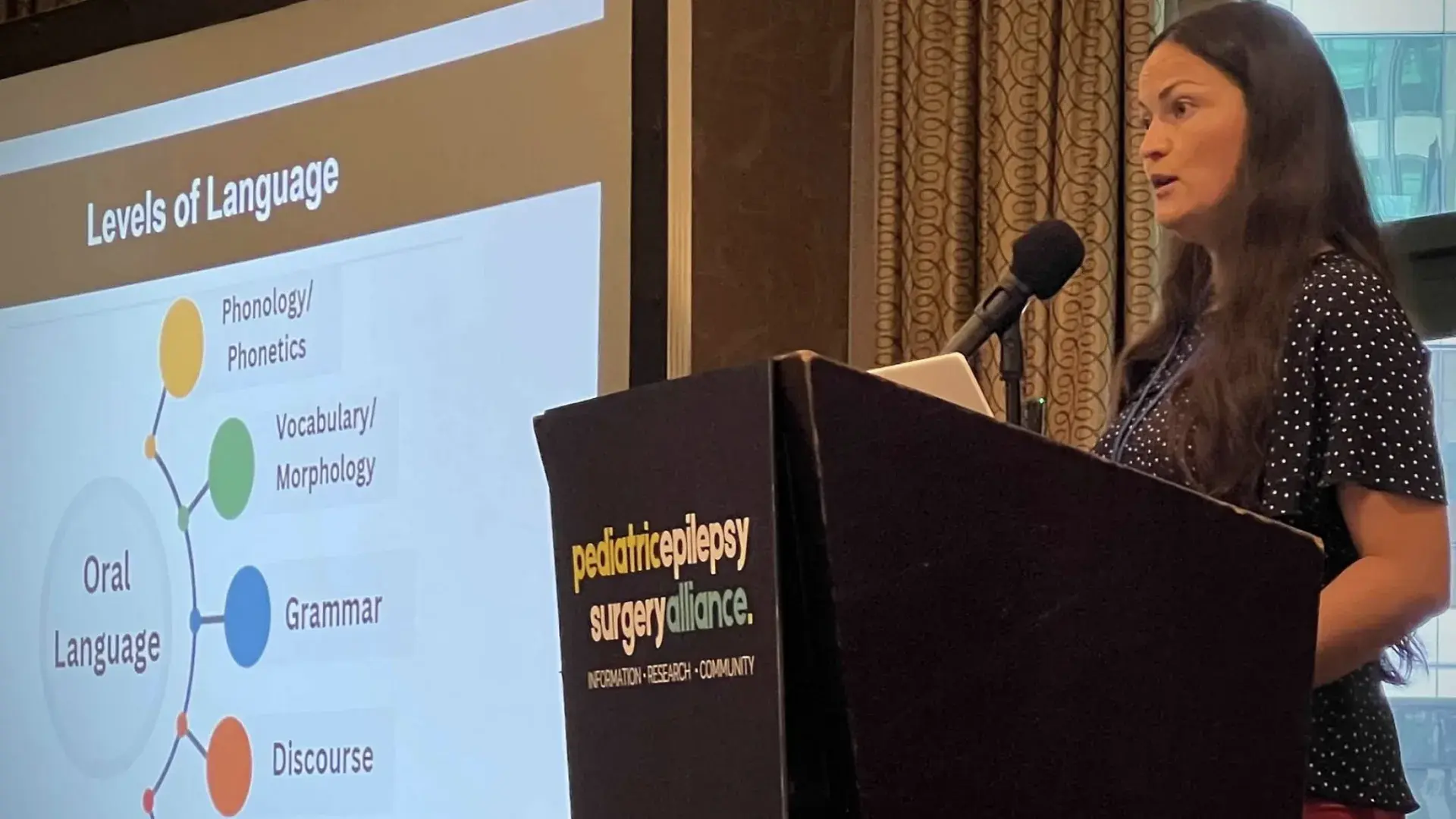

The study’s participants came to Boston this summer for a biennial conference held by the Pediatric Epilepsy Surgery Alliance (PESA), a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving the lives of children needing neurosurgery for drug-resistant epilepsy. Christodoulou has a 15-year history of working with the organization and its founder and president, Monika Jones.

“We are so thankful to PESA for the tremendous efforts they made to gather in Boston this year. Families from across the country made huge efforts to come to the gathering, and to join us for this research” recalled Christodoulou. “We are so grateful they made the extra effort to contribute to this study and that they shared their time, experiences, and stories with us.”

The conference is an opportunity for families to connect with one another and learn. “It's one of the few places these children have a chance to see someone else like them, to make a friend with someone who has been through a similar experience, and to be understood. So, it's an incredibly special gathering.”

The stakeholders in this research include not only parents and teachers but also clinicians, neurosurgeons, and neurologists.

“During the hemispherectomy surgery, surgeons are careful to attend to brain matter involved in seizure activity, while also trying to preserve core functions like motor and language skills where possible. We hope to learn whether the preservation (or disconnection) of particular white matter tracts, or the superhighways of the brain connecting regions, may be predictive of reading outcomes. This new knowledge could help inform surgery procedures to optimize brain matter that facilitates these children becoming stronger readers.”

Christodoulou and her team will spend the fall sifting through and analyzing the data; the first study is expected in December from Amy Maguire, a doctoral candidate in the PhD Rehabilitation Sciences program and graduate of the CSD program. Maguire served as the study interface between families, conference organizers, and researchers across MIT and MGH IHP, conducted 1:1 testing sessions with each participant, and attended the scans to ensure continuity of care. Her unique background working as a speech-language pathologist in neurosurgery at Massachusetts General Hospital prepared her well for this experience.

“The whole team was outstanding. There was an exceptional amount of coordination and collaboration needed to fit all the scans into a tight five-day window,” said Maguire. “The process of working alongside so many colleagues from IHP and MIT was inspiring and invigorating. I can’t emphasize how much of an honor it was to work with so many amazing families for this study.”

Christodoulou’s research team expects a series of studies to come out over the next few months, some of which may provide peace of mind by answering the question of why.

“In the context of hemispherectomy surgery, there are many unknowns as to what may come next, and why outcomes may differ across children,” said Christodoulou. “If we think about the range of reading outcomes and then relate it to specific brain architecture, you could say, ‘The reason they're not reading as well as you might hope is because the way that they're using their brain is really the best option they have given the architecture remaining.’ Similarly, for readers who are not easy to differentiate from their peers, we aim to understand what about their post-hemispherectomy brain architecture makes that possible.

“If we understand more about how brain pathways are set up and their association with reading skills, it might inform what instructional approach to use, what supports to provide, what reading trajectories to expect. Our hope is that this research gives us a lens through which to understand reading progress post-hemispherectomy to inform community members across medical, education, and clinical contexts.”

Do you have a story the Office of Strategic Communications should know about? If so, let us know.