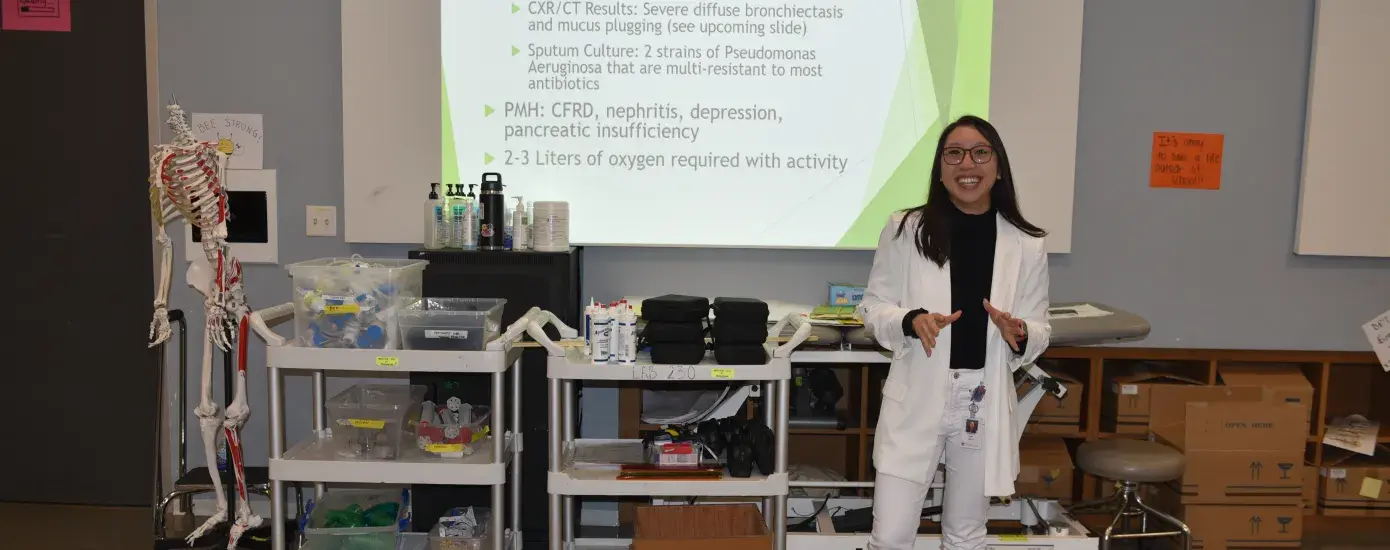

Rebecca Pham, a 2017 graduate of MGH Institute’s Doctor of Physical Therapy program, currently co-teaches the Cardiovascular and Pulmonary courses with Dr. Shweta Gore in the DPT curriculum and practices at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in the acute care setting. She has been looking at the challenges faced by people with larger bodies when it comes to healthcare and will be presenting on the topic, Reclaiming Fat: Unpacking and Dismantling Anti-Fatness in Healthcare at a conference of the Massachusetts Chapter of the American Physical Therapy Association on November 21. She spoke with OSC’s Lisa McEvoy for this month’s IHP Interview.

How did you get interested in the topic of weight stigma?

I've always been really interested in social justice issues, and I think a lot of the focus is on systemic barriers and health inequities as it relates to important issues like racism, sexism, and transgender care. The space around supporting patients with larger bodies is often left out of the conversation. Body positivity has gained a lot of traction in health and wellness spaces recently, but it doesn't really address underlying factors and structural factors that contribute to weight stigma and poor health outcomes for individuals who live in larger bodies.

When I was at the Brigham, we had a dietitian speak with us at one of our Grand Rounds about Health at Every Size. This is a health model around weight inclusive care that she practices, providing nutrition and dietary counseling to patients that is not focused on weight loss, because so much of the primary intervention for individuals who have diagnosed obesity is around weight loss as an individual behavioral modification through diet and exercise. The Health at Every Size philosophy really focuses on someone’s optimal goals for nutrition and exercise in a way that feels sustainable, feasible and authentic, with or without weight loss. If weight loss happens, there's no judgment around it. But that's not the primary focus. It focuses on things like your stress levels, your sleep quality, other metrics of health, like your blood glucose levels, your cholesterol levels, your blood pressures. And really the philosophy is around how we can improve health outcomes without focusing on weight loss.

Why is focusing on weight loss a problem?

While there is research that some people can perform weight loss and sustain it, these people are often the exception. Overwhelmingly, research shows that sustaining weight loss in the long-term is difficult. Most people who engage in weight loss undergo a process called weight cycling, where you lose weight and then you gain it back. And then you lose weight and then you gain it back. Typically, throughout that process, you gain more back than you lost in the first place. It's really hard to stick to diets. People struggle with them, and people also struggle with really regimented exercise routines. So much of it places a lot of personal responsibility on patients without examining other factors.

Focusing on weight brings up questions about what health inequities we’re creating when we're putting people on forced weight loss programs, or when we're having them engage in weight cycling, which places a lot of stress on the body and can contribute to developing chronic conditions like diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Additionally, when patients “fail” at weight loss, we reinforce a lot of negative messaging around shame, lack of willpower, low worthiness. This shame spiral contributes to an increased risk of depression and other ramifications on mental health. This can lead to engaging in behaviors that can negatively impact health, such as binge eating and other forms of disordered eating, avoiding physical activity, social isolation, and more.

Isn’t excess weight a health problem?

There's this idea that fat inherently is unhealthy and thin is inherently healthy, but we know that individuals across the size spectrum can experience chronic disease related to weight or not related to weight. This isn't to say that weight is never important, but that the weight-centric model of healthcare often focuses on weight as the lowest hanging fruit and views it as something that is really changeable and it's something that people should be able to change on their own. It doesn't account for structural things like socioeconomic status, where you live, what your work schedule is like, what conditions you're living in that could be contributing to your current weight status. And then there is just general body diversity. People exist in all different kinds of bodies.

While it seems to be generally accepted in research that excess body mass puts increased stress on joints, there's also discrepancies in that research. We know that correlation is not causation, but we often treat the relationship between health and weight as one of causation, when in reality, the relationship is much more dynamic and complex. We need to look at the way that we design research questions. If you already assume that fat is bad, that's going to drive how you design an experiment and ask a research question. When we research the consequences of excess weight, we often aren’t controlling for factors like weight stigma so the research itself is often biased.

There's this term, allostatic load, which is wear and tear on the body that happens with individuals from minoritized backgrounds experiencing racism. There's a physiological change happening in their bodies that chronically over time, repeated exposure to racism and living in racist environments directly impacts health. Similarly, there's research that weight stigma contributes to poor health outcomes.

When we say, ‘higher weight is associated with cardiovascular disease,’ if we're not accounting for how weight stigma contributes to that, then we think higher adiposity tissue directly is causing cardiovascular disease. And at the end of the day, it's an association. If they gained weight, they may have become more sedentary, and the weight gain might have been a part of that. But what was driving the increase in sedentary lifestyle was high stress. So maybe the stress is the driver and not the weight gain.

We have to focus on treating primary impairments if weight loss happens during that process, and if that's something that the patient finds is helpful and beneficial for them, that's fine. We want to move away from viewing weight loss as positive and optimal and viewing weight more neutrally so that we can decouple it from people’s sense of worth. We usually assume that weight loss is the only reason a person’s health improved, but maybe the story is more complicated than that.

What are some of the inequities associated with weight stigma?

There's research that weight stigma contributes to poor health outcomes. I mentioned earlier that weight stigma worsens behaviors like binge eating, for example. When we look at individuals in larger bodies, there is often an assumption that they are not exercising enough or not eating well, when this may or may not be the case.

Physicians and healthcare providers can take this myopic view. There's research that shows that healthcare providers spend less time examining individuals who are fat. They do not do as many tests and measures. So, if someone comes in with shortness of breath or back pain, they might immediately just say, ‘Oh, you just need to lose weight,’ but they won't actually run any labs. They won't do any imaging. Whereas, if a person who was thin came to them with the same complaints, then they would say, ‘You're thin, you're healthy. There must be another reason that's causing this.’

We get a lot of individuals who actually get misdiagnosed, and by the time something really urgent comes up, they still end up getting blamed because of their weight when it was actually due to medical malpractice and poor diagnostics from initial providers they saw.

There are surveys that show that many physicians view patients who are fat as lazy and less disciplined. They blame them for their chronic conditions. They view them as a burden to the health care. There's also research that shows that a lot of healthcare providers don't actually do hands-on examination of patients in larger bodies.

There are also inequities in research and equipment. Do we know how to take care of patients in larger bodies, and perform surgeries on patients in larger bodies? Are we researching medications and including these individuals in our research so that we can find the appropriate interventions that work for individuals across body types? Do we have the appropriate-sized beds, seats and waiting rooms, the right, correct size blood pressure cuffs? Individuals will often seek health care and the provider doesn’t have the proper equipment to even do any assessment around their physical condition.

They don't have access to the environment in the same way that individuals in thinner bodies do. Straight-sized is an alternative term referring to people who are not fat and this is referring to individuals who can access clothing in mainstream stores without difficulty and do not experience weight-related discrimination. What does weight-related discrimination look like? It looks like needing to pay more for things or being unable to access spaces and resources just because of the body that they're living in. Think about all these social structures of exclusion and isolation which impacts a community's ability to engage in physical exercise, to engage in health promoting behaviors. There are a lot of angles from which patients living in larger bodies are excluded from society, excluded from the healthcare space, excluded from education and hiring and employment. All of these things together are creating a picture where these individuals are facing multiple layers of oppression and marginalization that certainly impact their access to health care and their direct health.

What changes do you hope to set in motion with your presentation?

I have rarely been to any conferences or spaces where this is talked about explicitly, so our goal with bringing this presentation is really to raise awareness that it's even an issue and to educate physical therapy professionals.

We understand that individuals come in different bodies. We work with individuals with disabilities, but there is still a lot of ableism and weight centeredness in our PT profession. My personal take is that if a patient is coming to us asking for support with weight loss, there's a way that we can do it that's inclusive, but I don't necessarily think it's our role to tell patients to lose weight as a primary intervention. I know that this is something that others within our profession would say that we do have a role in, because we want to address chronic disease, and address the obesity epidemic. But again, by doing that, we're reinforcing stigmatization and not focusing on root causes and structural barriers for why these things are happening in the first place.

I would like to move towards a weight inclusive model, where we really believe that all individuals deserve quality, compassionate access and healthcare, regardless of their body size and weight. If we change the conversation to what are an individual's goals, how do we maximize a person's individual health goals? Is it that you want to walk further? Is it that you want to have less pain? Is it that you want to incorporate more vegetables into your routine? Is it that you want to be able to play with your grandchildren? We can provide interventions for all these things without coming from it at an angle of lose weight first and then all of these other things will be fixed. Everybody has a body; all bodies are good bodies and we all deserve to be safe in our bodies. That includes high quality healthcare regardless of weight status.

Do you have a story the Office of Strategic Communications should know about? If so, let us know.