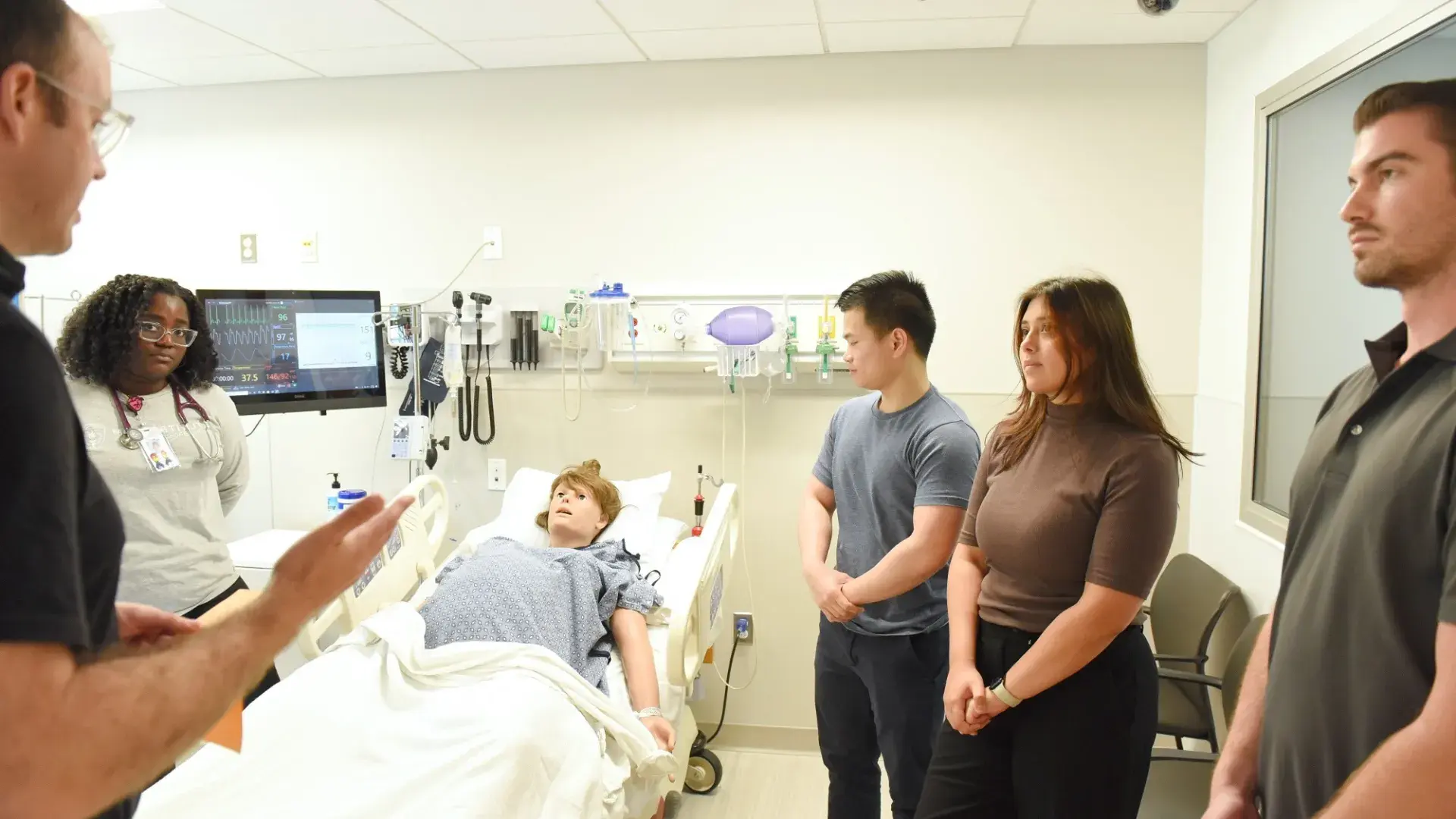

Using manikins, simulated participants, virtual reality, and AI, the MGH Institute is teaching students to provide comprehensive patient care.

Simulation can be nursing students treating a manikin that has a heartbeat and working lungs.

Simulation can be physician assistant students working with simulated participants played by actors.

Simulation can be interprofessional teams of students utilizing virtual technology to strengthen clinical or communication skills.

But no matter its form, simulation at the MGH Institute always means building on fundamentals to achieve cutting-edge education and innovative approaches to train students, develop educators, and strengthen team-based care or research practice.

Suzan Kardong-Edgren, a simulation expert and an associate professor of health professions education within the IHP School of Healthcare Leadership, says 2009 was a touchstone for the field. That’s when she joined the research team behind a two-year, randomized national study examining whether clinical training hours for prelicensure nursing students could be replaced by simulation.

The question was a pressing one for the study’s sponsor, the National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Nursing programs were competing for limited numbers of clinical training rotations. When rotations could be secured, the experiences they offered were inconsistent.

The study was completed with nearly 700 nursing students from 10 schools around the U.S., and its findings broke new ground.

“What we found,” Dr. Kardong-Edgren says, “was that you could safely substitute up to 50% simulation for traditional clinical—if we used high-quality, vetted scenarios with trained faculty who used a consistent debriefing methodology.”

Involved with the major simulation organizations—including the Society for Simulation in Healthcare and the International Nursing Association for Clinical Simulation and Learning— Kardong-Edgren has one eye on strengthening simulation practices and one eye on simulation’s future, including virtual reality with video-game style headsets and haptic gloves.

“My ultimate goal?” she says with a wry smile. “High-quality simulation for all.” “Simulations are designed to be learning spaces where students can make mistakes, learn from them, and try again, so that they can improve their skills through deliberate practice,” says Rachel Pittmann, the assistant dean of interprofessional practice. “Having a safe environment and a rapport with faculty is critical to learning. And debriefing afterwards is where all that learning gels.”

Simulation plays a vital role for students just beginning their education, notes Meaghan Clapp, an instructor of physician assistant studies.

“We’ve incorporated more simulation experiences with manikins and actors to better prepare our first-year students for the clinical rotations they’ll be doing in their second year,” she says.

And for second-year students who are doing clinical rotations, the department has added simulations to supplement their training, too. “Over the last few years,” Clapp explains, “we’ve identified areas and competencies that students don’t encounter at clinical sites, so we’re using simulation to address this.”

Simulations can also involve people modeling real-world clinical experiences.

“Through the IHP’s nursing program, we had what we call gynecological teaching associates,” Clapp says, referring to the actors who stand in as patients, also known as simulated participants (SPs). “A few years ago, I worked with simulation participant program manager Tony Williams, and we were able to build a group of male teaching associates, so our students were able to learn about both female and male exams.”

Williams is an expert stage manager. He consults with faculty, juggles educational objectives, and recruits and trains SPs. Some of these actors are retired nurses, doctors, and physical therapists, or trained stage and screen actors. Others are newcomers who he trains from scratch.

Williams helps make simulations feel real enough to help students learn and experience the “Aha!” moments that will help them become better providers. One key achievement has been creating a diverse pool of actors to better simulate the patient pool that IHP graduates are likely to serve, especially patients whose first language is not English

“Traditionally, simulations invite students to guess what a patient’s diagnosis is,” Williams says. “But health care is much more comprehensive and has so many more elements, so we don’t just limit simulation to diagnostic procedures. We simulate conflict resolution, microaggressions, interprofessional education, and delivering bad news.

“We’re working toward a unified approach to healthcare simulation instead of being siloed and compartmentalized,” he continues. “We’re seeing more use of SPs across the Mass General Brigham system in continuing education programs and to train staff, helping current, experienced healthcare professionals to continue to grow and adjust to society’s needs.”

Meeting these needs is a crucial part of assistant professor of nursing Maureen Hillier’s simulation work, which stretches from classroom instruction to tackling tough social problems. Dr. Hillier, a certified healthcare simulation educator, brings her students to the Simulation Lab in the Shouse Building to learn about pediatrics, where care can be highly specialized to meet the needs of children of all ages who have different medical conditions.

In one simulation, the patient is a “baby,” a manikin with computer-generated symptoms. The baby’s parent is played by a convincingly anxious actor. Another simulation features a six-year-old boy, also a manikin, who is neurologically atypical. He’s a foster child, and he’s having trouble breathing.

Hillier’s students ask questions, make diagnoses, communicate with “family members,” and work with colleagues. Afterwards, students debrief, reflecting on what they did, what they learned, and what they might do differently.

“We can also make things happen in simulation classes that students may not encounter on their clinical rotations,” Hillier says, such as ensuring that every nursing student is exposed to conditions like dehydration and restricted airways.

“The biggest benefit is that there’s no risk of harming patients,” she says. “It’s a low-stakes learning environment that gives students the opportunity to become better.”