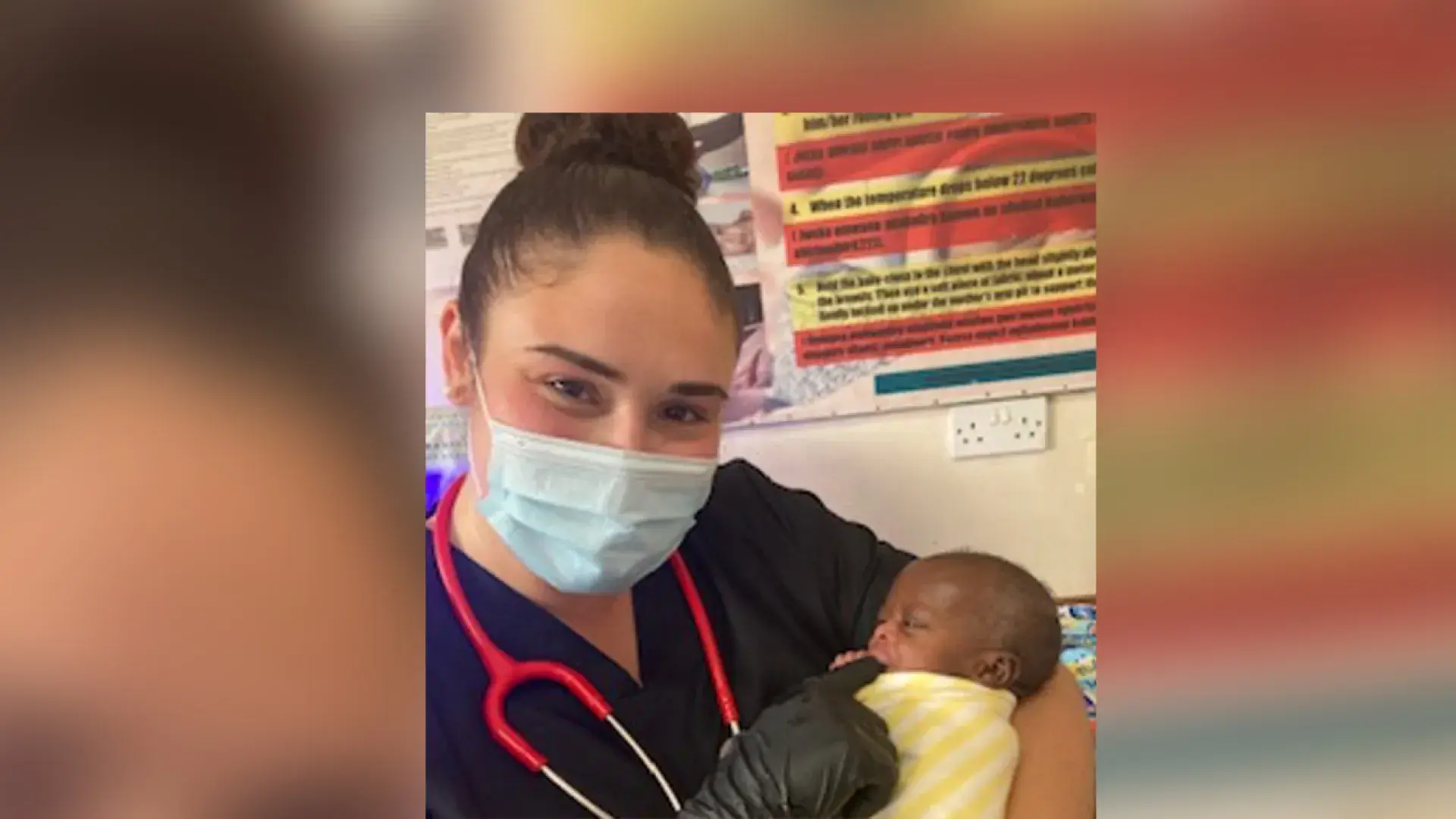

It was on her second day in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in Uganda’s Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital that Leah Rothchild’s plans for what she wants to do as a nurse practitioner completely shifted.

“We lost a baby,” says the second-year student. “I was doing the resuscitations when we called it off and decided to let the baby pass.”

Until then, she had planned to go into pediatric mental health. But this being the first time Rothchild, a mother of a young girl herself, endured the death of a patient first-hand, she knew she never wanted to stop caring for infants. “That was the moment I realized I wanted to stay in the NICU,” she recalled.

“There was so much that family endured during their hospital stay that I couldn’t imagine going through as a parent,” she says. From washing their clothes in buckets behind the NICU to providing the hospital the medical tape that secured their baby’s IV cannula, Rothchild was struck by the various unique experiences the infant and their family encountered in Uganda that they would not have faced in a hospital in the U.S. “At times, it was hard to relate to them, but then you see the love they have for their child and the pain of their loss. That’s universal.”

The first IHP student to join School of Nursing instructor and clinical lab coordinator Jennifer Duran on her first trip back to Uganda since the pandemic, Rothchild spent two weeks training the hospital’s nurses and nursing students, conducting patient assessments, and providing direct patient care.

“Global health has always been a passion of mine,” says Rothchild, whose goal is to one day provide health care on each of the Earth’s seven continents. “I’ve gone on global health trips before and I have always loved immersing myself in a culture and truly understanding the needs of those in front of me.”

For Rothchild, the two-week trip was both eye opening and life changing.

“You can research patient care in settings like Mbarara and watch documentaries, but nothing prepares you to see such resource limitations first-hand,” says Rothchild, who noted how rolling blackouts greatly affected patient care. “It’s an unparalleled experience.”

Rothchild watched as Mbarara nurses and doctors were constantly forced to go without adequate supplies. Sometimes it was a piece of equipment that Rothchild knew would make a procedure easier, other times it was a missing medication that Rothchild could get at the tip of her fingers while doing her clinical rotations.